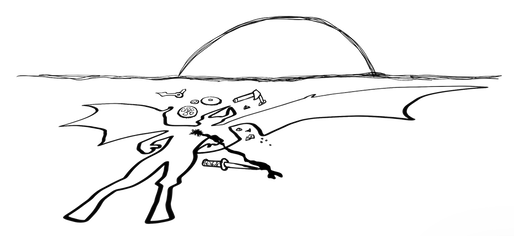

Demon

How do we begin to unthink the idea of the world as a machine?

The first thing we’ll need to do is to slay a beast: the demon invoked by Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1814.

Laplace’s demon is a hypothetical entity that knows precisely where all the particles in the universe are right now, and where they are going next. In more accurate (but also more technical) terms: it knows (with unlimited accuracy) the position and momentum of all the particles which make up the present state of the universe. Given this knowledge and the laws of classical physics known at the time of Laplace, the demon can reconstruct the state of the universe at any time in the past and predict it at any time in the future.

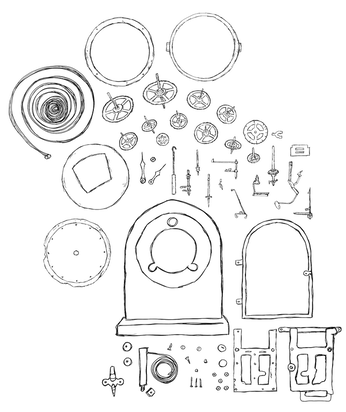

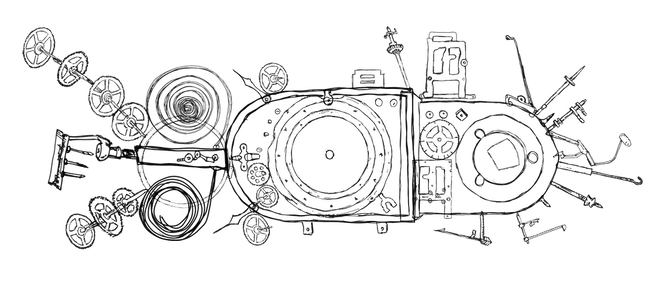

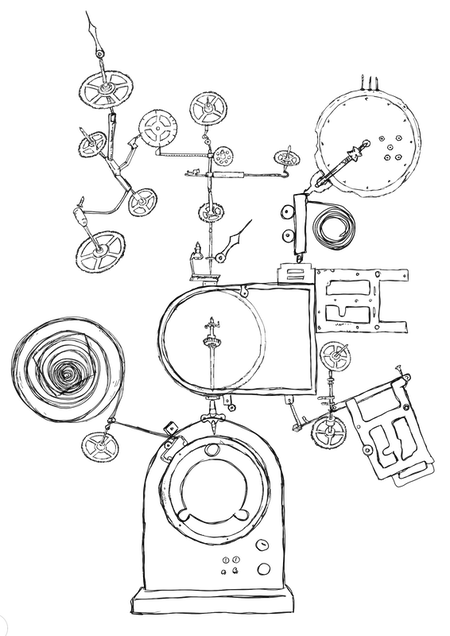

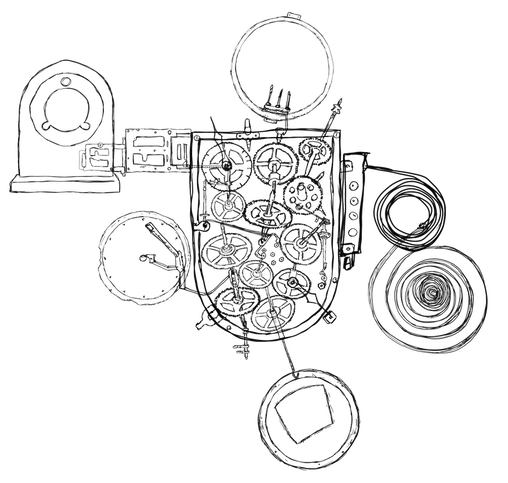

Laplace’s demon is an anthropomorphised metaphor for a much more abstract concept: causal determinism. It is the idea that everything in the universe necessarily occurs according to the laws of physics. Causal determinism is the ultimate machine view, treating the world as a high-precision clockwork that always progresses according to a predetermined blueprint. We can disassemble this machine-world into discrete parts — the cogwheels, springs, and ratchet of the clock — their workings comprehensively comprehensible. To know how the clock works, we just put the pieces together again.

How do we begin to unthink the idea of the world as a machine?

The first thing we’ll need to do is to slay a beast: the demon invoked by Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1814.

Laplace’s demon is a hypothetical entity that knows precisely where all the particles in the universe are right now, and where they are going next. In more accurate (but also more technical) terms: it knows (with unlimited accuracy) the position and momentum of all the particles which make up the present state of the universe. Given this knowledge and the laws of classical physics known at the time of Laplace, the demon can reconstruct the state of the universe at any time in the past and predict it at any time in the future.

Laplace’s demon is an anthropomorphised metaphor for a much more abstract concept: causal determinism. It is the idea that everything in the universe necessarily occurs according to the laws of physics. Causal determinism is the ultimate machine view, treating the world as a high-precision clockwork that always progresses according to a predetermined blueprint. We can disassemble this machine-world into discrete parts — the cogwheels, springs, and ratchet of the clock — their workings comprehensively comprehensible. To know how the clock works, we just put the pieces together again.

The demon’s world is a closed place in which nothing truly new ever happens. Everything is predictable or can be reconstructed, at least in principle. This appears to be a comforting and desirable vision for some — especially, we guess, those orderly souls who do not delight in mysteries and surprises.

Personally, we find this Laplacean vision abhorrent. It is stifling, claustrophobic. There can be no real freedom or personal responsibility in such a closed and deterministic world. Indeed, there cannot be true life, as we shall see. Ultimately, it is a vision of a barren universe, utterly dead and dull.

Luckily, we now know that the demon is not scientifically plausible. There are many physical reasons why this is the case. Both quantum mechanics and the theory of measurement impose fundamental limits on the precision at which the position and momentum of the universe’s components can be determined. Moreover, either theory implies that we will never be able to measure the whole state of the universe all at once, because who’s to measure the measurer? In addition, quantum indeterminacy and deterministic chaos fundamentally restrict our ability to predict the future (both in their own, very different, way). Last but not least, entropy imposes an irreversibility on energy-transforming processes that is not reflected in the time-reversible laws of either classical or quantum mechanics. Irreversibility means that information is lost over time, which renders the reconstruction task of the demon impossible. And we have not even started to talk about black holes, spacetime singularities that irretrievably devour information (among all kinds of other things made of energy and matter), or cosmic inflation, which descends like a dark screen over the earliest moments of our cosmological past, rendering it completely impenetrable to us.

In reality, Laplace’s demon can neither reconstruct the past nor predict the future. It is neither a coherent idea, nor consistent with what contemporary physics tells us about the world. The strong determinism it implies is a myth, a fairy tale, not a scientific fact about the world.

Personally, we find this Laplacean vision abhorrent. It is stifling, claustrophobic. There can be no real freedom or personal responsibility in such a closed and deterministic world. Indeed, there cannot be true life, as we shall see. Ultimately, it is a vision of a barren universe, utterly dead and dull.

Luckily, we now know that the demon is not scientifically plausible. There are many physical reasons why this is the case. Both quantum mechanics and the theory of measurement impose fundamental limits on the precision at which the position and momentum of the universe’s components can be determined. Moreover, either theory implies that we will never be able to measure the whole state of the universe all at once, because who’s to measure the measurer? In addition, quantum indeterminacy and deterministic chaos fundamentally restrict our ability to predict the future (both in their own, very different, way). Last but not least, entropy imposes an irreversibility on energy-transforming processes that is not reflected in the time-reversible laws of either classical or quantum mechanics. Irreversibility means that information is lost over time, which renders the reconstruction task of the demon impossible. And we have not even started to talk about black holes, spacetime singularities that irretrievably devour information (among all kinds of other things made of energy and matter), or cosmic inflation, which descends like a dark screen over the earliest moments of our cosmological past, rendering it completely impenetrable to us.

In reality, Laplace’s demon can neither reconstruct the past nor predict the future. It is neither a coherent idea, nor consistent with what contemporary physics tells us about the world. The strong determinism it implies is a myth, a fairy tale, not a scientific fact about the world.

Determinism

To better understand why, we must examine what it means for the universe to be deterministic. As it turns out, there are two versions of causal determinism: strong and weak. Laplace’s demon represents the strong version of determinism: given the way things are right now, we can reconstruct exactly how they were in the past and we can know for certain how they will be in the future.

Weak determinism, in contrast, simply says that every effect must be determined by one or more causes. Nothing happens from nothing, without any rhyme or reason. It is not true that anything goes in this world. There are rules and regularities. But weak determinism is weak because it allows for non-deterministic influences and a loss of information over time. In other words, it is perfectly compatible with the view that the effects of some causes have vanished without a trace, that some things happen more or less randomly (that is, not in a lawlike manner), and that we cannot always know what will happen next (although we can usually reconstruct, looking back after the fact, what happened and how it happened).

Weak determinism implies that we can never know everything about the world. Our knowledge will always be partial and approximate. First, things that should not have been forgotten, were lost. Second, not all events in the world are lawlike, not all facts about the world explainable by general principles. Third, the future is constrained by what happened in the past and present, yet also fundamentally open at the same time. There is a radical asymmetry regarding past and future. As we will see, these limitations on what we can know are not just a temporary reflection of our human cognitive limitations, biases, errors, and lack of foresight. They are fundamental properties of a large world we engage with as limited observers.

What is more plausible, strong or weak determinism? Isn’t the business of science to predict and control, to strive for certainty? The answer we give to this last question is a clear “no.” The purpose of science is to understand and explain, to gain trustworthy (not absolute) knowledge of the world. This does not presuppose or imply in any way that the world is predictable or controllable.

In fact, as we have seen above, Laplacean strong determinism flies straight in the face of what we actually know about the world. It not only lacks any empirical support, but stands in stark contradiction to contemporary physics.

You’d think the case is closed: Laplace’s demon, poor thing, is dead, buried, and surely forgotten by now. And yet, it stubbornly refuses to stay dead. Like a zombie, it comes back, time and again, each upgrade more subtle and beguiling, harder to recognize for what it really is.

Its most recent incarnation is the popular belief, among researchers and the wider public alike, that every physical process is some kind of computation. There is a not-so-subtle distinction we need to make here: we are not dealing with the idea that we can approximate physical processes by computer simulations (a perfectly reasonable position), but that the world literally is one big digital or quantum computer. Bazinga! The demon is back.

We will give you a precise definition of what we mean by computation in due time. For now, just think of it as manipulation of symbols, what your computer does when it runs a program, or what you do when you solve a maths problem with pen and paper according to some step-by-step instructions.

If everything is a computation, then everything can be computed. And if you can compute something, it is predictable. Is it not? This question defines a famous problem, which is called the decision problem (or Entscheidungsproblem). It keeps logicians and theoretical computer scientists awake at night. It will keep us busy as well, for many chapters to come. The decision problem is what makes this contemporary version of the demon much more subtle than its classical incarnation. This demon is more powerful than its predecessors because it can seemingly explain why only some phenomena in the universe behave in a law-like manner, while others are impossible to predict or deduce from general laws.

The reason is that the decision problem itself is undecidable in general. I know, it’s ironic. Alonzo Church and Alan Turing proved this fundamental mathematical result in two independent publications in 1936. In our context, it means that some computational processes can only be evaluated by actually running them step by step. There is no way to take a short cut, to skip some of the computational iterations and predict what the computation will do. And this is a real problem because many computations take an intractably large amount of time and effort to perform. Some, in fact, would take longer than the age of our actual universe!

Such processes are computationally complex, or irreducible. This concept of “complexity” is only one of many we will encounter in this book. In the context of computation, complexity (irreducibility) is defined by our (lack of) ability to compress a process into a shorter sequence of steps. At the same time, this means that an irreducible computation exhibits no regular or law-like behaviour (otherwise, we could compress it, after all).

The overarching problem is that we cannot decide in advance which computational processes are irreducible and which ones are not. Given two sets of rules, we cannot even predict, in general, whether they will carry out the same computation or not. Most of the time, we have to actually run them, step by step. Basically, finding out which processes in the universe are law-like and which ones are not, which ones are equivalent to others and which ones are unique, cannot be done on first principles. It is largely an empirical question. We, limited beings, have to work it out the hard way: by trial and error. This turns out to be laborious and slow, much slower than the processes we try to understand. So we’re always lagging a few steps behind.

The demon, however, is not constrained in this way. It knows everything. It is not limited by computational power, or our restricted outlook on the world. Therefore, it is still able to reconstruct the past and predict the future precisely, given the rules governing universal computation and the world’s present state. Quantum computing is even better: with it, the demon will not only predict the actual future of the universe, but all possible futures! The only difference to Laplace’s original version is that there are now strict and explicit limits on what a limited observer like us can achieve from within a computational universe. Nevertheless, this is still strong determinism overall, even if it is weak in all practical aspects.

Now you may ask: why should such a purely speculative distinction matter? It does, because the modern, computational demon represents a powerful idealisation that still strongly influences the way we think about how we ought to get to know the world. It lives on in the assumption that scientific knowledge should at least aspire to the ideal of completeness and certainty. Even if we know it is not possible in practice for us limited beings, it is what we should try to approximate as closely as we possibly can.

To better understand why, we must examine what it means for the universe to be deterministic. As it turns out, there are two versions of causal determinism: strong and weak. Laplace’s demon represents the strong version of determinism: given the way things are right now, we can reconstruct exactly how they were in the past and we can know for certain how they will be in the future.

Weak determinism, in contrast, simply says that every effect must be determined by one or more causes. Nothing happens from nothing, without any rhyme or reason. It is not true that anything goes in this world. There are rules and regularities. But weak determinism is weak because it allows for non-deterministic influences and a loss of information over time. In other words, it is perfectly compatible with the view that the effects of some causes have vanished without a trace, that some things happen more or less randomly (that is, not in a lawlike manner), and that we cannot always know what will happen next (although we can usually reconstruct, looking back after the fact, what happened and how it happened).

Weak determinism implies that we can never know everything about the world. Our knowledge will always be partial and approximate. First, things that should not have been forgotten, were lost. Second, not all events in the world are lawlike, not all facts about the world explainable by general principles. Third, the future is constrained by what happened in the past and present, yet also fundamentally open at the same time. There is a radical asymmetry regarding past and future. As we will see, these limitations on what we can know are not just a temporary reflection of our human cognitive limitations, biases, errors, and lack of foresight. They are fundamental properties of a large world we engage with as limited observers.

What is more plausible, strong or weak determinism? Isn’t the business of science to predict and control, to strive for certainty? The answer we give to this last question is a clear “no.” The purpose of science is to understand and explain, to gain trustworthy (not absolute) knowledge of the world. This does not presuppose or imply in any way that the world is predictable or controllable.

In fact, as we have seen above, Laplacean strong determinism flies straight in the face of what we actually know about the world. It not only lacks any empirical support, but stands in stark contradiction to contemporary physics.

You’d think the case is closed: Laplace’s demon, poor thing, is dead, buried, and surely forgotten by now. And yet, it stubbornly refuses to stay dead. Like a zombie, it comes back, time and again, each upgrade more subtle and beguiling, harder to recognize for what it really is.

Its most recent incarnation is the popular belief, among researchers and the wider public alike, that every physical process is some kind of computation. There is a not-so-subtle distinction we need to make here: we are not dealing with the idea that we can approximate physical processes by computer simulations (a perfectly reasonable position), but that the world literally is one big digital or quantum computer. Bazinga! The demon is back.

We will give you a precise definition of what we mean by computation in due time. For now, just think of it as manipulation of symbols, what your computer does when it runs a program, or what you do when you solve a maths problem with pen and paper according to some step-by-step instructions.

If everything is a computation, then everything can be computed. And if you can compute something, it is predictable. Is it not? This question defines a famous problem, which is called the decision problem (or Entscheidungsproblem). It keeps logicians and theoretical computer scientists awake at night. It will keep us busy as well, for many chapters to come. The decision problem is what makes this contemporary version of the demon much more subtle than its classical incarnation. This demon is more powerful than its predecessors because it can seemingly explain why only some phenomena in the universe behave in a law-like manner, while others are impossible to predict or deduce from general laws.

The reason is that the decision problem itself is undecidable in general. I know, it’s ironic. Alonzo Church and Alan Turing proved this fundamental mathematical result in two independent publications in 1936. In our context, it means that some computational processes can only be evaluated by actually running them step by step. There is no way to take a short cut, to skip some of the computational iterations and predict what the computation will do. And this is a real problem because many computations take an intractably large amount of time and effort to perform. Some, in fact, would take longer than the age of our actual universe!

Such processes are computationally complex, or irreducible. This concept of “complexity” is only one of many we will encounter in this book. In the context of computation, complexity (irreducibility) is defined by our (lack of) ability to compress a process into a shorter sequence of steps. At the same time, this means that an irreducible computation exhibits no regular or law-like behaviour (otherwise, we could compress it, after all).

The overarching problem is that we cannot decide in advance which computational processes are irreducible and which ones are not. Given two sets of rules, we cannot even predict, in general, whether they will carry out the same computation or not. Most of the time, we have to actually run them, step by step. Basically, finding out which processes in the universe are law-like and which ones are not, which ones are equivalent to others and which ones are unique, cannot be done on first principles. It is largely an empirical question. We, limited beings, have to work it out the hard way: by trial and error. This turns out to be laborious and slow, much slower than the processes we try to understand. So we’re always lagging a few steps behind.

The demon, however, is not constrained in this way. It knows everything. It is not limited by computational power, or our restricted outlook on the world. Therefore, it is still able to reconstruct the past and predict the future precisely, given the rules governing universal computation and the world’s present state. Quantum computing is even better: with it, the demon will not only predict the actual future of the universe, but all possible futures! The only difference to Laplace’s original version is that there are now strict and explicit limits on what a limited observer like us can achieve from within a computational universe. Nevertheless, this is still strong determinism overall, even if it is weak in all practical aspects.

Now you may ask: why should such a purely speculative distinction matter? It does, because the modern, computational demon represents a powerful idealisation that still strongly influences the way we think about how we ought to get to know the world. It lives on in the assumption that scientific knowledge should at least aspire to the ideal of completeness and certainty. Even if we know it is not possible in practice for us limited beings, it is what we should try to approximate as closely as we possibly can.

Hubris

What could possibly be wrong with this ideal? It does seem like a good thing.

Should we not strive for the most trustworthy knowledge possible? Indeed, we should! And, since we never know in advance just how good our knowledge could get, is it not reasonable to aspire to an unattainable but at least identifiable goal? Should we not always strive for perfection?

The problem is that we sometimes forget that absolute knowledge is not only impossible, but also not really desirable. This is now no longer a problem of physics or computation, but a problem of epistemology, the philosophical theory of knowledge.

The undead demon is described in the opening chapter of William Wimsatt’s excellent “Re-engineering Philosophy for Limited Beings”. If you only ever read one philosophy book in your life, why not make it this one? Wimsatt agrees with us (actually, we agree with him) that certain knowledge is an unrealistic ideal for a science pursued by limited beings, under real-world conditions and in real time, with the cognitive and technological tools actually available. In fact, Wimsatt writes, it is not just unrealistic but outright misleading, and that is why the ideal of certain knowledge is undesirable.

One major issue is that Laplace’s demon cannot exist within our universe. For it to have complete knowledge of all particles, it must be outside the world, looking in. Otherwise, some particles always remain unobserved, unmeasured, because they are what is doing the measuring — they are the demon. They are what is doing the observing. Therefore, Laplace’s beast cannot be a natural being. It is not made of the same stuff as the rest of the universe. It is supernatural: much more like a god than any imaginable real investigator who must study the world while being an intrinsic (and generally quite tiny) part of it. That god’s eye view of the world the demon gets? It does not exist. It is unreal.

This is the simple crux of the matter: if you want certain knowledge, then science is not your best choice. Instead, go to church! Join a cult. Have a revelation.

Although much less obviously murderous than your average religious fanatic, believers in absolute scientific truth and technological solutions for everything may ultimately be as bad for the future of humanity as any fundamentalist reactionary. It will likely be an overestimation of our own capacities that brings about humanity’s downfall.

One of the largest problems afflicting late modern society is hubris. If we forget that we are not like the demon at all, then we forget that we are human. We will see how this mistake still creeps into all kinds of discussions within and about science, even today.

This is why the demon must die. It must be killed and buried properly. It must no longer be allowed to come back from the grave. The idea that the universe behaves and, in fact, is just like the latest technology we’ve invented – whether clockworks or computers, all perfectly analysable, understandable and controllable – is completely featherbrained. The pipe dream that we can ever get a “view from nowhere” on the universe, a complete and objective outlook, must be thoroughly purged from our minds. Laplacean omniscience does not represent at all how we get to know the world. Not even remotely like it.

We are no god looking at reality from outside. It is extremely unlikely that we will ever understand the world completely. In fact, we do not even know what that could possibly mean. There goes predictability, certainty, control. There goes omniscience. The world is not Laplacean, not a clockwork, not a simulation. It is not a machine. It is not small and ultimately knowable. Quite the contrary, the world is unfathomably large, richer than we will ever comprehend, and radically open ended. We will always keep on learning more about it, as long as we exist. And it will keep on surprising us in ways we would never have expected.

Pursuing the ideal of certain knowledge, of absolute control, of complete predictability, is not an exalted or noble activity. It is delusional at a very deep level. And it is still frighteningly common, especially among people who put a lot of trust in human ingenuity and technological innovation. These are people who would like to engineer reality, who would like to fix and handle it like a machine. Sadly, that won’t go well. Remember those unintended consequences? They're always there, and rarely a good thing. It is and remains humanity’s job to adapt to reality, not the other way around.

Again: don’t get us wrong. We agree that we should try to attain the most trustworthy knowledge possible. We should always strive to innovate and improve our technology. We are not anti-science or anti-technology here. That would be silly. We shall never stop exploring this wonderful and mysterious world. We shall never give in to ignorance.

But we should not overestimate what we can know, and what we can do. It is as important to recognize our limitations, as it is to recognize our achievements, especially in a time when our technological capability to destroy ourselves far exceeds our capability to act wisely and sustainably. We must rediscover our own bounds, and we’d better do it soon.

What could possibly be wrong with this ideal? It does seem like a good thing.

Should we not strive for the most trustworthy knowledge possible? Indeed, we should! And, since we never know in advance just how good our knowledge could get, is it not reasonable to aspire to an unattainable but at least identifiable goal? Should we not always strive for perfection?

The problem is that we sometimes forget that absolute knowledge is not only impossible, but also not really desirable. This is now no longer a problem of physics or computation, but a problem of epistemology, the philosophical theory of knowledge.

The undead demon is described in the opening chapter of William Wimsatt’s excellent “Re-engineering Philosophy for Limited Beings”. If you only ever read one philosophy book in your life, why not make it this one? Wimsatt agrees with us (actually, we agree with him) that certain knowledge is an unrealistic ideal for a science pursued by limited beings, under real-world conditions and in real time, with the cognitive and technological tools actually available. In fact, Wimsatt writes, it is not just unrealistic but outright misleading, and that is why the ideal of certain knowledge is undesirable.

One major issue is that Laplace’s demon cannot exist within our universe. For it to have complete knowledge of all particles, it must be outside the world, looking in. Otherwise, some particles always remain unobserved, unmeasured, because they are what is doing the measuring — they are the demon. They are what is doing the observing. Therefore, Laplace’s beast cannot be a natural being. It is not made of the same stuff as the rest of the universe. It is supernatural: much more like a god than any imaginable real investigator who must study the world while being an intrinsic (and generally quite tiny) part of it. That god’s eye view of the world the demon gets? It does not exist. It is unreal.

This is the simple crux of the matter: if you want certain knowledge, then science is not your best choice. Instead, go to church! Join a cult. Have a revelation.

Although much less obviously murderous than your average religious fanatic, believers in absolute scientific truth and technological solutions for everything may ultimately be as bad for the future of humanity as any fundamentalist reactionary. It will likely be an overestimation of our own capacities that brings about humanity’s downfall.

One of the largest problems afflicting late modern society is hubris. If we forget that we are not like the demon at all, then we forget that we are human. We will see how this mistake still creeps into all kinds of discussions within and about science, even today.

This is why the demon must die. It must be killed and buried properly. It must no longer be allowed to come back from the grave. The idea that the universe behaves and, in fact, is just like the latest technology we’ve invented – whether clockworks or computers, all perfectly analysable, understandable and controllable – is completely featherbrained. The pipe dream that we can ever get a “view from nowhere” on the universe, a complete and objective outlook, must be thoroughly purged from our minds. Laplacean omniscience does not represent at all how we get to know the world. Not even remotely like it.

We are no god looking at reality from outside. It is extremely unlikely that we will ever understand the world completely. In fact, we do not even know what that could possibly mean. There goes predictability, certainty, control. There goes omniscience. The world is not Laplacean, not a clockwork, not a simulation. It is not a machine. It is not small and ultimately knowable. Quite the contrary, the world is unfathomably large, richer than we will ever comprehend, and radically open ended. We will always keep on learning more about it, as long as we exist. And it will keep on surprising us in ways we would never have expected.

Pursuing the ideal of certain knowledge, of absolute control, of complete predictability, is not an exalted or noble activity. It is delusional at a very deep level. And it is still frighteningly common, especially among people who put a lot of trust in human ingenuity and technological innovation. These are people who would like to engineer reality, who would like to fix and handle it like a machine. Sadly, that won’t go well. Remember those unintended consequences? They're always there, and rarely a good thing. It is and remains humanity’s job to adapt to reality, not the other way around.

Again: don’t get us wrong. We agree that we should try to attain the most trustworthy knowledge possible. We should always strive to innovate and improve our technology. We are not anti-science or anti-technology here. That would be silly. We shall never stop exploring this wonderful and mysterious world. We shall never give in to ignorance.

But we should not overestimate what we can know, and what we can do. It is as important to recognize our limitations, as it is to recognize our achievements, especially in a time when our technological capability to destroy ourselves far exceeds our capability to act wisely and sustainably. We must rediscover our own bounds, and we’d better do it soon.

Humility

What then can a limited being, a natural investigator, realistically hope for? According to Wimsatt, it is not perfect knowledge, but piecewise approximations to reality.

This means that our situation isn’t as simple as we may have thought, but it is also far from hopeless. Not everything is just arbitrary discourse, not everything some devious game of power, without any reach or relevance outside our shifting social constructions and interrelations. Wimsatt writes that science is the “best-crafted repository of truth on this planet”, and we wholeheartedly agree.

Humans are able to gain knowledge about the rich and messy world we live in, knowledge that is both trustworthy and generalizable. That’s what science does and, when done properly, it does it really well.

At the same time, our grasp always remains limited to some degree, our models and theories abstracted, simplified, and idealised, open to future extension and revision. We can be wrong, deluded even, as we are a bit at this point in history, as we shall see. To avoid this, we constantly re-engineer what we know through a cumulative, adaptive process aimed at improving our grip on reality.

In this way, we can create order and predictability – we can control our world – but only to some extent, and we must humbly accept that such authority is only ever local, approximate, and temporary. If we forget this, our delusions of grandeur can easily become fatal.

Laplace’s demon, in all its guises and reincarnations, fosters such delusions by hiding the basic fact from us that all knowledge of the world must be derived from our particular and imperfect relations with it. Our knowledge must keep on adapting as we encounter the world in ever-changing ways. But worst of all: the demon makes us sometimes forget that what we want is human knowledge. This is not a bug, but an essential feature of our way of getting to know the world. A certain lack of objectivity is not always a bad thing, in the sense that we want knowledge that is relevant to us, in our particular human condition.

This is how any natural, limited being gets to know the world. Not just humans. Nobody alive is observing reality objectively, from an outside vantage point. We learn by being immersed in experience, by actively encountering the world. No living organism is remotely like the demon. We are all right in the middle of it, deeply embodied and engaged, never left untouched. And, in the end, we are all tiny and insignificant in the great scheme of things. The world is much larger than all of us together.

Aspiring to an ideal of absolute certainty is absurd. In fact, it is foolish because it loses much of the essential characteristics of actual knowledge production under realistic circumstances. And it is dangerous because it makes us forget our idiosyncrasies and limits.

Because the world is large, the process of experiencing it in new ways never ends. It is clearly impossible, not only for humans, but for any imaginable natural observer (no matter how highly evolved or superintelligent) to get a god’s-eye perspective on the world.

The knowledge of any living being is always deeply relational in ways that the demon’s objectivity is clearly not. As we shall see, the beast’s omniscience is not only impossible, incoherent, but it is also completely irrelevant. Once you know everything about your world, nothing really matters anymore. The demon is not only a god, it is also a machine, devoid of any sign of life or meaning.

To understand this better, we need to talk next about why our world is large, while the world of machines and omniscient demons is small, no matter how numerous and diverse the parts it is made of, or how enormous its physical dimensions are.

What then can a limited being, a natural investigator, realistically hope for? According to Wimsatt, it is not perfect knowledge, but piecewise approximations to reality.

This means that our situation isn’t as simple as we may have thought, but it is also far from hopeless. Not everything is just arbitrary discourse, not everything some devious game of power, without any reach or relevance outside our shifting social constructions and interrelations. Wimsatt writes that science is the “best-crafted repository of truth on this planet”, and we wholeheartedly agree.

Humans are able to gain knowledge about the rich and messy world we live in, knowledge that is both trustworthy and generalizable. That’s what science does and, when done properly, it does it really well.

At the same time, our grasp always remains limited to some degree, our models and theories abstracted, simplified, and idealised, open to future extension and revision. We can be wrong, deluded even, as we are a bit at this point in history, as we shall see. To avoid this, we constantly re-engineer what we know through a cumulative, adaptive process aimed at improving our grip on reality.

In this way, we can create order and predictability – we can control our world – but only to some extent, and we must humbly accept that such authority is only ever local, approximate, and temporary. If we forget this, our delusions of grandeur can easily become fatal.

Laplace’s demon, in all its guises and reincarnations, fosters such delusions by hiding the basic fact from us that all knowledge of the world must be derived from our particular and imperfect relations with it. Our knowledge must keep on adapting as we encounter the world in ever-changing ways. But worst of all: the demon makes us sometimes forget that what we want is human knowledge. This is not a bug, but an essential feature of our way of getting to know the world. A certain lack of objectivity is not always a bad thing, in the sense that we want knowledge that is relevant to us, in our particular human condition.

This is how any natural, limited being gets to know the world. Not just humans. Nobody alive is observing reality objectively, from an outside vantage point. We learn by being immersed in experience, by actively encountering the world. No living organism is remotely like the demon. We are all right in the middle of it, deeply embodied and engaged, never left untouched. And, in the end, we are all tiny and insignificant in the great scheme of things. The world is much larger than all of us together.

Aspiring to an ideal of absolute certainty is absurd. In fact, it is foolish because it loses much of the essential characteristics of actual knowledge production under realistic circumstances. And it is dangerous because it makes us forget our idiosyncrasies and limits.

Because the world is large, the process of experiencing it in new ways never ends. It is clearly impossible, not only for humans, but for any imaginable natural observer (no matter how highly evolved or superintelligent) to get a god’s-eye perspective on the world.

The knowledge of any living being is always deeply relational in ways that the demon’s objectivity is clearly not. As we shall see, the beast’s omniscience is not only impossible, incoherent, but it is also completely irrelevant. Once you know everything about your world, nothing really matters anymore. The demon is not only a god, it is also a machine, devoid of any sign of life or meaning.

To understand this better, we need to talk next about why our world is large, while the world of machines and omniscient demons is small, no matter how numerous and diverse the parts it is made of, or how enormous its physical dimensions are.

|

Previous: The Age of Machines

|

Next: A Large World

|

The authors acknowledge funding from the John Templeton Foundation (Project ID: 62581), and would like to thank the co-leader of the project, Prof. Tarja Knuuttila, and the Department of Philosophy at the University of Vienna for hosting the project of which this book is a central part.

Disclaimer: everything we write and present here is our own responsibility. All mistakes are ours, and not the funders’ or our hosts’ and collaborators'.

Disclaimer: everything we write and present here is our own responsibility. All mistakes are ours, and not the funders’ or our hosts’ and collaborators'.